Every new technology can be used for good or ill.

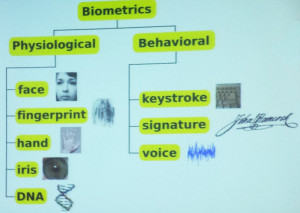

Such is the case with the newly developing field of behavioral biometrics, a technology that’s not the same as the “biometrics” many of us know well. The chart below (provided by security expert Per Thorsheim) differentiates the two categories.

As you can see, behavioral biometrics uniquely identifies you by your actions (“what you do”) rather than your physiology (“what you are”). Signature and voice recognition are examples familiar to everyone. But I hadn’t heard of identifying people by their keystrokes until I recently attended a talk on the subject by Thorsheim at PasswordsCon (which he founded).

How it works

Whether you type on a conventional keyboard or a touchscreen display, researchers have found, you tend to follow certain patterns of movement and timing. These may vary a bit from one occasion to the next, but they are consistent enough to characterize you as an individual. Differences have been observed, says Thorsheim, even between how men and women type. (Patterns have also been found in how individuals swipe touchscreens and move their computer’s pointing device.)

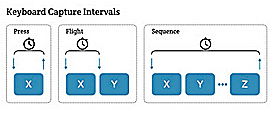

Here are some examples of the kind of data that can be collected while you type. It includes how long you press any single key and how long it takes you to move from one key to another or press a particular sequence of keys. (Source: BehavioSec)

The good news

Using such information, fraud and identity theft prevention products have been able to distinguish between legitimate users and imposters with a high degree of accuracy. For example, in a pilot project at a bank, Swedish security company BehavioSec says, it was able to correctly identify both legitimate users and imposters 99.7% of the time.

And when such information is combined with traditional password authentication, it becomes a form of two-factor authentication that can offer better security than using a password alone. Because the data collection is invisible to the user, it’s painless and more convenient for the user than having to offer a fingerprint, reply to a text message, or enter a special security code (also known as a token).

The down side

Keystroke data could also fuel a privacy threat. If, say, a company like Facebook or Google maintained a massive database linking keystroke patterns to specific individuals, that data could be used by anyone who obtained access to it—a criminal, the company’s business partners, or someone working for a government agency–to identify that person even when they used a different device, such as a friend’s computer. In light of the amount of tracking and surveillance to which the public has already been subjected, the potential for abuse of this technology is worrisome.

There is no evidence that anyone is yet amassing such a database. Still, Thorsheim has given this challenge some thought and, together with fellow researcher, Paul Moore, developed a Chrome browser plug-in called Keyboard Privacy to defeat keystroke profiling. It camouflages your keystroke data, making it harder for the website to pin down a clear pattern. Based on some of the early user reviews of this plug-in, I suggest that anyone considering giving this plug-in a try have serious technical expertise.

While we may not yet need this kind of privacy-protection tool, our experiences with browser cookies, targeted advertising, and other online tracking technologies suggests that it is a good thing that someone is already thinking about and working on this problem. One of these days, we may well need such a tool.

—Jeff Fox